CONTENT

Translations

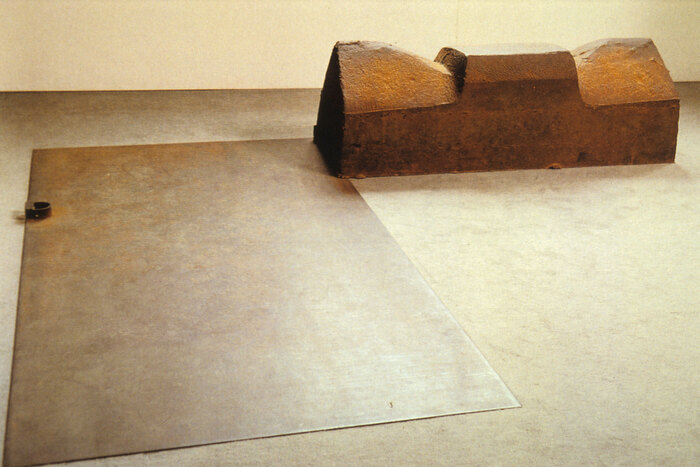

A horizontal field inside a building – its supposed border is slowly fading from a yellow colour into its surroundings. A space, which is made out of a precious material: hazelnut powder.

A different work: a small room, its walls are covered with an orange material. Its uneven surface contains spots of a darker colour – a space made out of bee wax, lit up by small lamps.

Another work: a number of volumes of different scales and geometries made of bee wax, rice or milk. The volumes convey the idea of pyramids, house-like-buildings or other constructions. Sometimes palisades or other wooden structures support them; sometimes they are just positioned on the ground accompanied by small crops of another material.

A different work: a small room, its walls are covered with an orange material. Its uneven surface contains spots of a darker colour – a space made out of bee wax, lit up by small lamps.

Another work: a number of volumes of different scales and geometries made of bee wax, rice or milk. The volumes convey the idea of pyramids, house-like-buildings or other constructions. Sometimes palisades or other wooden structures support them; sometimes they are just positioned on the ground accompanied by small crops of another material.

©

©

All those works are part of the oeuvre of Wolfgang Laib. They are built with materials produced by animals or plants which have been collected in most parts by hand over the course of several decades in the countryside around his small home village in the German Alps.

The preciousness of the material, the essentiality of the execution, is combined in a movement of translation from one space into another. The meditating practice of collecting pollen one flower after the other is complemented by the meditating practice of disposition: a sieve or scraper, a couple of days, tens of hours, an almost static position of the body and minimal repetitive movements of manual labour. The contemplative dimension of an installation as extension of the contemplative experience of collecting and of disposing.

The works of Wolfgang Laib are translations from one space into another space: from the spaces of the alpine countryside, from trees, bushes or meadows, from plants, cows or bee hives into the emptiness of a building made out of concrete, bricks or iron, sometimes dark, sometimes bright, sometimes introverted, but sometimes defined just by a structure of steel and a layer of glass separating the installation from the outside. Wolfgang Laib’s works are movements of compaction and displacement, from one spatial condition – from the flower, udder or honeycomb – into another spatial condition, into fields, spaces, volumes or other devices. These are practices of translation which act in time and place. They consist of the miraculous moment when a shower of pollen falling on the ground, when a layer of wax applied to the wall, or compacted to a small volume, ceases to be mere collected matter and becomes a field, a room, a house.

This translation is made possible by the patience, perseverance and coherence of working practice and not by semiotic systems. A certain kind of knowledge accumulates during the whole process while at the same time superfluous thoughts are swept away.

As a matter of fact designing very often means to transport pieces of knowledge between different spaces. Creative solutions, certain ensembles, materials, tools or procedures, which have been effective somewhere else, are put in action in order to verify their effectiveness in a new material setting.

It happens that we encounter suggestions in other places, in other situations, in other media, in other dimensions, scales or material realms, while we are trying to give an answer to a more or less precise question. In fact the discipline of architecture as well as all the other areas of design practice have to be understood in the framework of all the disciplines which exist parallel to them and with which they exchange continuously. Developments, which occur outside of architecture, are channelled through the discipline, through its precise set of conventions, instruments and rules, in order to verify them.

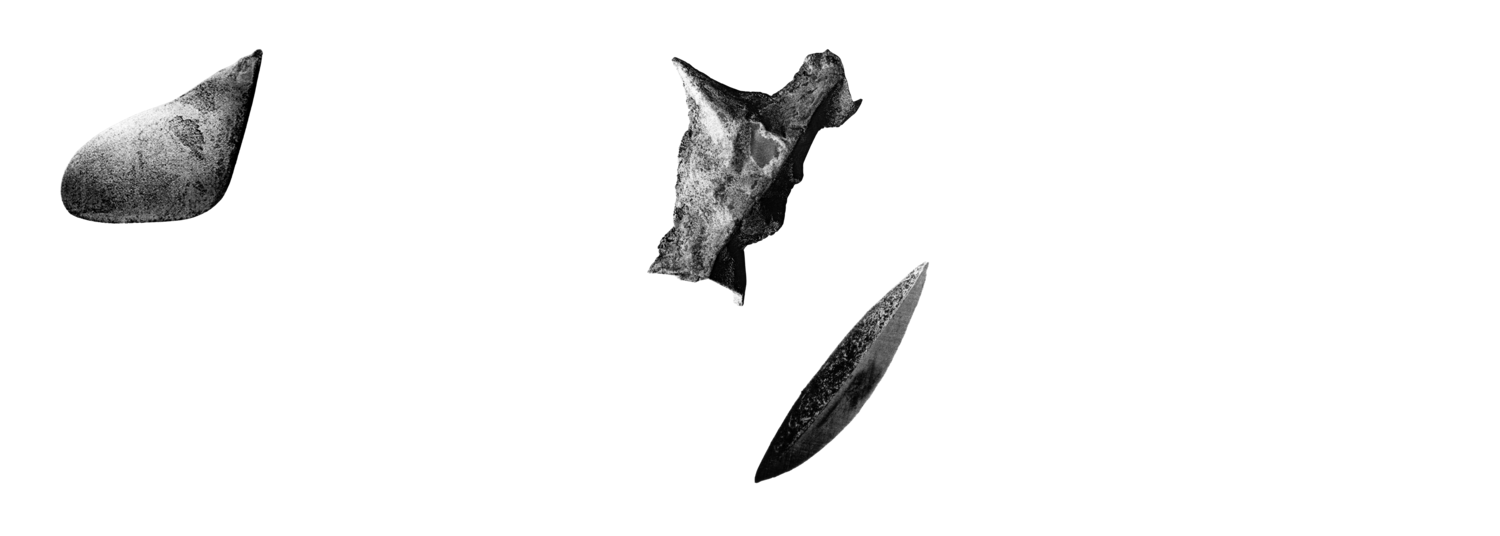

In each project, in each design practice, movements of translation and compression happen, which displace pieces of knowledge between different cultural realms. Sometimes the geometry of a shell found on a beach influences the geometry of the ceiling of a church. These translations happen outside of the realm of systemic thought, they are never abstract but always concrete, they are always specific, what works here, does not work there.

It occurs that two pieces of iron become a building and a lake, but from a different point of view the same volume might become a series of mountains.

It happens that two volumes of wax become two buildings and a space in between. Later or to a different viewer they are just two pieces of wax.

Sometimes a couple of wooden sculptures inside a building become a set of columns while later becoming the scenario of a futuristic city.

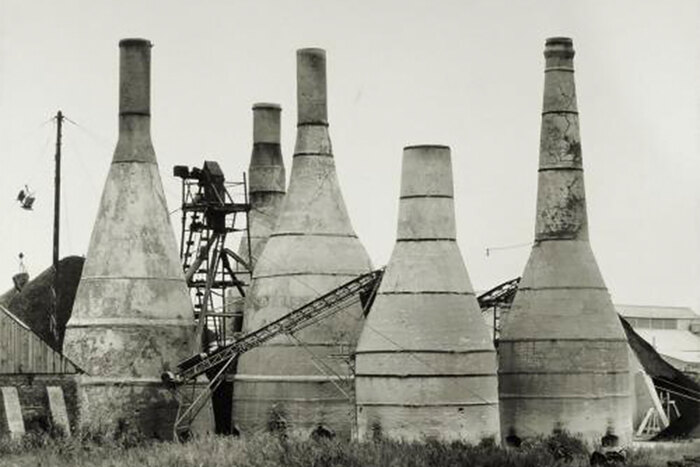

Sometimes a set of very high concrete volumes becomes a series of skyscrapers. In fact size does not matter, it does not matter whether the whole or only parts are visible, it is the way of looking at things that counts.

Sometimes a piece of marble becomes a terrain with an ensemble of buildings.

Sometimes the same material becomes an artificial landscape and a building. Conversely, sometimes it occurs that a building or set of buildings become a sculpture.

Sometimes the precise drawn dehoir of a multilevel parking becomes the scenario of the Californian landscape.

It is possible that pieces of knowledge travel from one practice to another, from one space to another, in this translation movements of expression might survive the displacement from one plane to a different one, but quite often the forces of displacement and compression which are part of this movement, while trying to shift relations from one place to another, force the pertaining plane of expression to rearticulate itself.

Eventually these translations are effective only for fragments and only under certain circumstances, and what is more important – there exists no theory, no formula, it is not repeatable, quite often it resembles a moment of Eureka! a sudden court circuit.

©

©

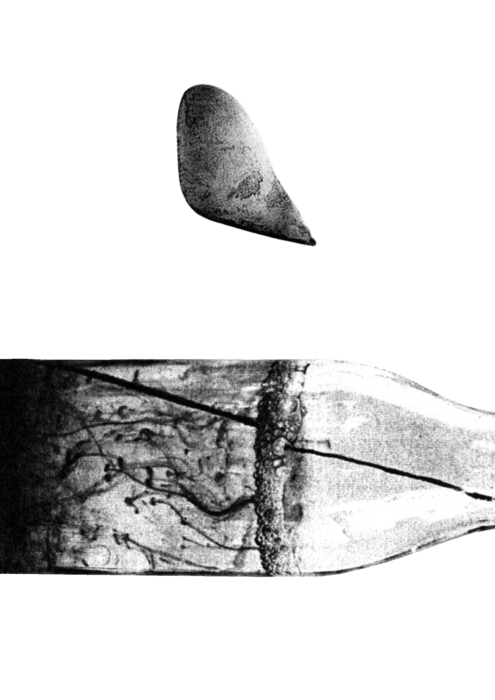

Therefore sometimes a collection of bottles resembles a series of buildings. Sometimes a series of buildings resemble a collection of bottles. But quite often a collection of bottles resemble just a collection of bottles.

With Le Corbusier we could say, that eyes, which are able to see, can perceive the architectural in almost everything. Eyes, which are able to watch, to observe, to see permit to imagine, to invent and to create. And as always in the applied arts, with mastery comes the possibility to do almost everything.

The most direct connection between thought and practice is of uttermost importance for design practice. Any possible theoretical overheat, formula, common places, methods, that get in between inventive thought and creative practice, makes this immediacy impossible. There is no innocence of using one for the other. In this case not even mastery saves the day.

But watch out! A painting is a painting, an abstract painting is an abstract painting, there is no way of taking it for anything else. It is no facade or whatever. It is a painting on a canvas, usually displayed on a wall; it even has a canvas around it. A sculpture is a sculpture, there to be experienced. A drawing of a house is precisely the drawing of a house and not the house. No one less than Magritte tells us that everything tends to suggest that there is little relationship between an object and its representation.

The difference between the two is about the difference between abstract theory and concrete material practice. Whereas in abstract thought – the same as in rendering – everything is possible, material practices position themselves in the framework of all the other material practices, architecture is positioned in the framework of all the other applied arts, especially the visual arts, of landscape and of the applied sciences. In doing so movements of exchange occur continuously between creative practices which are more or less explicit, but never 1:1.

Stephan Jung

KEYWORDS

AVAILABLE

SAFT 06 PARALLELS

is also available as part of:

Buy it now !